Dave Mellor, AlphaPlus’ Director of Assessment shares his thoughts on the challenges of closing the virtuous circle of teaching, learning and formative assessment.

When teachers plan their lessons, they set out what they expect their class to know or be able to do at the end of the lesson. However just because a teacher has taught a topic or skill, it doesn’t necessarily mean that the learner has learnt the knowledge or developed the skill successfully.

The difference between teaching and learning is illustrated in the conversation below where a split class is taught by two teachers who are coordinating their work:

Teacher 1: What did you do in class today?

Teacher 2: I did the past tense but I am not sure what the students did!

Whatever is taught by the teacher isn’t necessarily learned by the learners. There are barriers in communication and understanding which may get in the way of learning, and consolidation is often needed by the learners to embed the teaching and help them understand it. Good classroom practice should help with all of that but there can be a significant barrier to this being successful and it is often not clear to the teacher whether the learners have learnt what was taught.

Formative assessments are used to help understand what learners know and can do, and help identify areas of learning which are strengths and areas of learning where additional support through some sort of intervention may be needed. A well designed formative assessment will help the teacher target the gaps in learning that they need to address in their teaching. These formative assessments can be short quizzes or tests in class, worksheets or online activities for homework or more structured assessments at the end of topics or even end of term or year. They all give feedback to the teacher about the individual learners’ abilities.

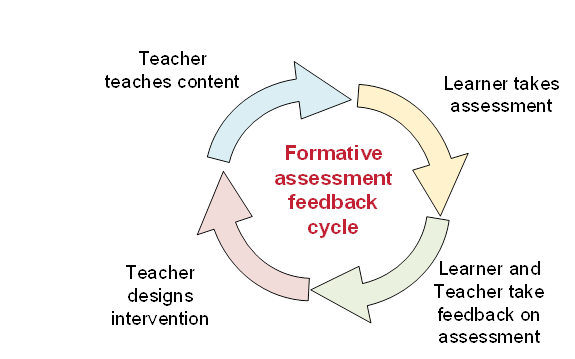

The diagram below illustrates the idealised feedback process where the formative assessment provides the feedback on the learning to allow the teacher to identify and fill any gaps in learning.

However using this information can be a significant challenge for the teacher, if the learners are of different abilities (that is, they know and can do different things). Delivering personal intervention to a class of 30 learners is not easy to manage given the resource and time constraints in classrooms.

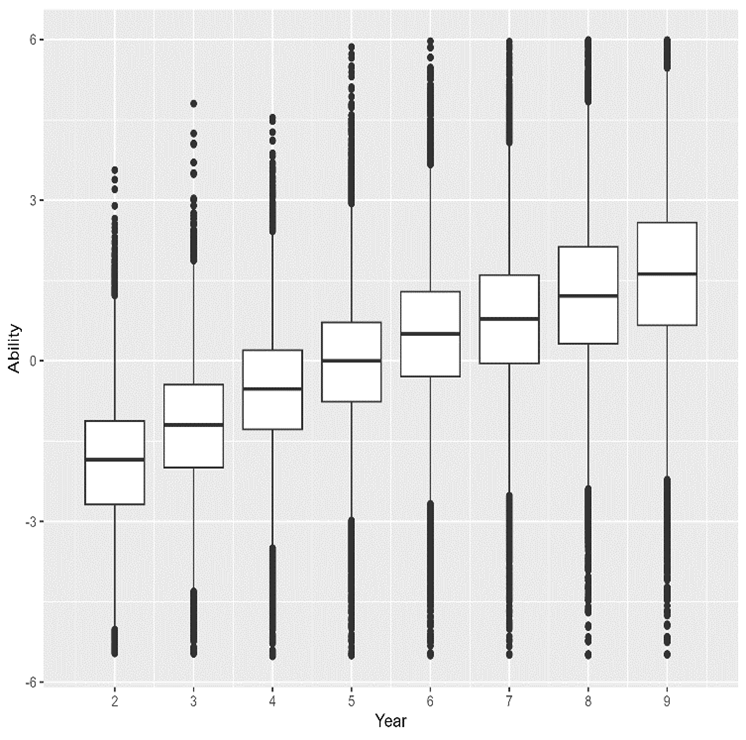

In the different national adaptive assessments in literacy and numeracy that we deliver for two UK governments, we see a far greater spread in the ability of the learners (i.e. what they know and can do) than the difference in ability from one year group to the next (as illustrated in the diagram below). In fact, the ability of the learners at the top of a year will be greater than the ability of average learners five years above. Whilst an individual school or class may not reflect the full spread of ability in the national picture, the spread of ability in a class will still be far wider than the difference in ability between year groups in a school in almost every case.

Feedback from formative assessments is most useful when it is highly specific to the individual learner. However, in many instances, teachers are only able to apply interventions to a whole class of learners due to limitations in the time and resource available. When the variation of the ability of the class is as wide as it can be (see diagram above), then a whole class intervention is unlikely to succeed in addressing the needs of all of the learners. There is a danger that the lowest ability learners get left behind and the highest ability learners become disengaged as they already know or can do what is required.

The challenge is therefore how the feedback loop can be closed successfully. There are a number of possible solutions to this which have been applied in different circumstances. For example:

- In secondary school, learners can be streamed into classes or groups of similar ability so that they can be taught content which is suitable for them. This may work to some degree but it does not address the fact that different learners may have different strengths and weaknesses in different areas of the content.

- In primary school learners for some subjects could be split by ability rather than age. So all of years three to six are taught Literacy or Numeracy at the same time and they are split by ability and not age. However, though it does better accommodate the wide spread of abilities within a year, it does not deal with the fact that different learners may have different strengths and weaknesses and their different life experiences may also be a barrier.

- Interventions are only designed for the lowest ability learners to try and get them up to speed with where the curriculum says they should be. This can often be at the expense of their learning in other areas of the curriculum, e.g. focus on maths instead of a perceived less important subject and is at the expense of every learner achieving their potential which is the aim of most modern curricula.

There is no simple answer to this problem if the role of the teacher is as the provider of knowledge that the learner then learns (as is traditional). Personalised learning that aims to help learners address their areas of weakness and build on areas of strength is difficult to deliver in this way, particularly when a teacher has 30 learners, each with their own educational needs.

So are there any alternatives?

A possible alternative is to have a set of topic-linked online resources which contain clear learner journeys. A diagnostic assessment can ascertain the learners’ strengths and weaknesses and they can engage with the online teaching and learning materials, either individually or in small groups of similar ability learners. The teacher guides the students along their pathways, coaches them if they get stuck and encourages the development of team working, self-reliance and self-regulation and resilience. The learning can be assessed through small, formative end of lesson and end of topic online assessments and interventions identified which the teacher or the learning programme can then deliver to address gaps.

This would be a fundamental change to the way that much teaching and learning takes place and would require significant resourcing in the underpinning infrastructure. However, unless we are able to move away from the teacher providing the instruction to the whole class, then we are unlikely to be able to fully solve the problem of successfully using information from formative assessment and close the virtuous feedback loop of teaching, learning and formative assessment.

If you would like to know more about our experiences of delivering formative assessments or have any thoughts on what could be done to help close the virtuous circle of teaching, learning and assessment then please do get in contact with us.

AlphaPlus

AlphaPlus